you may invest your humanity."

- Albert Schweitzer

Critical Essay by

Nancy M. Martin

Professor and Chair, Department of Religious Studies

Director, Schweitzer Institute

Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) has inspired generations of students, faculty, staff and friends of Chapman University in his commitment to service to humanity and his philosophy of reverence for life. A theologian, philosopher, musician, and then medical doctor, he embodied the interdisciplinarity and commitment to life-long learning that have been ideals of education at Chapman from its earliest days. He insisted on self-honesty and the pursuit of truth without regard to how it might challenge our most cherished assumptions, as well as humility with respect to the always limited nature of our knowledge.

Schweitzer earned doctorates in both theology and philosophy, while at the same time becoming an acclaimed concert organist. Recognizing his own privilege and the many people, known and unknown, who had made it possible for him to pursue these talents and passions, he wanted to actively serve others, to “pay it forward” so to speak, and he also keenly felt the debt that Europeans and Americans owed to Africa because of the horrors of the slavery. At the age of thirty, already with an established career, he undertook medical studies to become a doctor and chose to go to Gabon under the auspices of a missionary society but decidedly not as a missionary. They accepted him under two conditions—he had to raise all the funding himself and they forbade him to preach because of his unorthodox theology. This was fine with Schweitzer—he only wanted to be a doctor. In the wake of WWI, he questioned the usefulness of philosophical debates. He was searching for a fundamental grounding for ethical behavior that might be compelling to all people, regardless of religion or the lack thereof. He would call his solution “reverence for life,” and he would set out to make his life his argument.

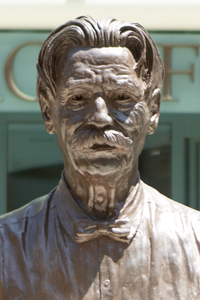

Reverence for life entails not only the preservation of physical existence but also a deep respect for the will to live in all beings and a commitment to foster the flourishing of humans as well as all other forms of life. With respect to human beings this requires that we do all that we can to promote the self-actualization of each person, the opportunity to fully develop their individual talents and passions, whatever they might be. Necessarily this means that all humans must have sufficient nourishment, clothing, and shelter as well as education, healthcare, security and autonomy to do so. Thus, the pursuit of human rights and justice for all necessarily flows from these commitments. To truly embody reverence for life, each person must develop within themself the virtues of authenticity, gratitude, and compassion, and Schweitzer encouraged each individual to find “a place to invest their humanity.” Many came all the way to Africa to meet him, including Valerie Scudder to whom this bust is dedicated, and he took time to talk with each person, encouraging them to discover and pursue their own “project of love.”

He received the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work in 1952 but felt that he must do something more to deserve it. Although he preferred to avoid politics, he was persuaded that the dangers to all life from nuclear weapons required him to act. He did so, presenting a reasoned, evidence-based scientific argument for why even testing such weapons endangered all life on earth. Marshalling his considerable intellect and moral influence, he was instrumental in securing the international test ban treaty. His scientific approach was a key inspiration to Rachel Carson in her groundbreaking study of the impact of pesticides, The Silent Spring (1962), which inspired the environmental movement in the United States. Schweitzer’s refusal to establish a hierarchy of value of living beings also continues to resonate with the care ethics and biocentrism of eco-feminists and other environmentalists into the twenty-first century.

Albert Schweitzer has been criticized on a number of grounds. He has been falsely accused not only of being a Christian missionary out to “save souls” rather than to heal bodies, but also of being a communist because of his opposition to nuclear weapons during the Cold War. His motivations have been questioned, as has his seeming lack of interest in learning African languages and culture, choosing instead to continue his philosophical work after hours. Some have also criticized the nature of the hospital. People came from hundreds of miles to seek his aid, and they and their families needed to be housed and fed during the period of treatment, so the hospital had to function like a village, and those who were able were asked to participate in the daily labor of keeping the hospital going. Schweitzer was further criticized for not employing and training more African staff, the hospital functioning primarily on volunteer labor even as it did on donations from abroad.

Schweitzer did much to enlighten Americans and Europeans in the early twentieth century with respect to the humanity and dignity of African people. Even so, like ourselves, Schweitzer could not fully escape the implicit racism of his time. He is rightly criticized particularly for his stance on African independence, suggesting that because colonial powers had so thoroughly destroyed the social structure and values of village life, they should remain to assist Africans in the transition to full autonomy. However, as the respectful letters he exchanged with W. E. B. Du Bois make clear, Du Bois admired Schweitzer’s commitment and agreed with Schweitzer that the initial phases of independence would likely be very difficult but nevertheless necessary for African dignity and autonomy, and Schweitzer expressed a sincere desire to learn from Du Bois about the wider global dynamics and history—a conversation they would never be able to have. In 1962, Schweitzer argued publicly against United Nations and American intervention in Congo on the grounds of African peoples’ rights to self-determination.

Albert Schweitzer, in his life and philosophy, continues to be a source of inspiration to live with reverence for all life and in service to others and a reminder that self-honesty, humility, and the willingness to learn and change are essential to living with authenticity.

Works on Schweitzer by Chapman faculty:

Meyer, Marvin and Bergel, Kurt, eds. Reverence for Life: The Ethics of Albert Schweitzer for the Twenty-First Century. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2002.

Martin, Mike W. Albert Schweitzer’s Reverence for Life: Ethical Idealism and Self-Realization. Burlington: Ashgate, 2007.